Background

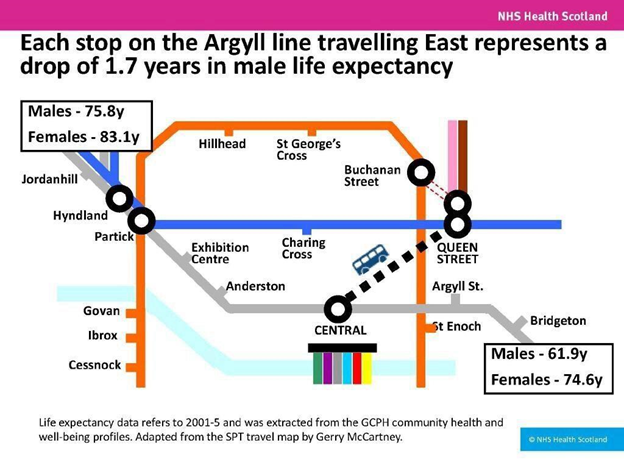

Professor Jason Leitch opened #Quality2019 with a familiar yet profound illustration of the equity challenges faced by health systems across the world.

At #Quality2019, Professor Jason Leitch showed very clearly how health inequality is written across the face of our cities. Quality improvement must work for Bridgeton. © NHS Scotland

As #Quality2020 was postponed from earlier this year, and the agenda was set pre-pandemic, the issue of equity in health has been brought into sharper focus. Health inequality is clearly measured in the catastrophic statistics or mortality and long term harm. Has the pandemic affected our priorities and activities in reducing inequity in health care? How can we make sure that efforts to improve equity are not forgotten in the chaos?

In the opening keynote of #Quality2020, Don Berwick posted a timely reminder – there is no Quality without Equity:

#Quality2020 6 new paths into a better normal…@KedarMate and @donberwick keynote during this year’s Forum pic.twitter.com/WFIhAR9IKD

— Pedro Delgado (@okpedrodelgado) November 2, 2020

The new abnormal

It has been well documented from early on in the pandemic that COVID-19 disproportionately impacts people who are already disadvantaged. They will also bear the brunt of the long term impact on the economy and health. [Pan 2020, Razaq 2020] Retrospective analysis of the data from the first wave in England confirms that ethnicity, comorbidity and household size should be priorities in future planning. [de Lusignan S 2020]

So improving health equity is now a society-wide crisis. But is this adequately reflected in what we’re doing? Are minorities represented in the decision-making processes, policy and planning? That’s a rhetorical question, by the way.

Briefly, a sobering anecdote. Many of the systematic reviews I encountered in researching this blog reported that ethnicity was not recorded or analysed. It turns out this is not just an anecdotal finding. Digging further, I came across a systematic review of skin symptoms in COVID-19 that found no (yes, no) studies that used images of dark skin to illustrate dermatological manifestations of the disease. [Lester 2020] This is an extraordinary omission.

Of course, this blind spot doesn’t just affect clinical studies. A review of clinical standards reported substantial variation in how ethnicity was prioritised in crisis planning. [Cleveland Manchanda 2020] Clearly, we need to improve the reporting and prioritisation of equity-related factors. Let’s see how #Quality2020 can help equip us for the task.

Sessions and speakers

B5: Urgent action on improving equity

Yvonne Coghill, NHS England; England

Pedro Delgado, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; UK

In this live session, Yvonne Coghill and Pedro Delgado took up these pressing questions.

First, they clarified the important distinction between equity and equality. Equity means that everyone should have the same opportunity to achieve good health. In contrast, equality is treating everyone equally, offering everyone the same opportunity, ignoring the fact that the starting point may not be the same. In other words, achieving equity is a precondition to reaching equality. Pedro explores this in more detail on this blog.

They also provided some concrete guidance and practical tools to help us move towards ensuring more equal access to care.

[Recording of session on Livestream]

Although the specifics of inequity vary geographically, the impact is consistent:

Inequity means harm.

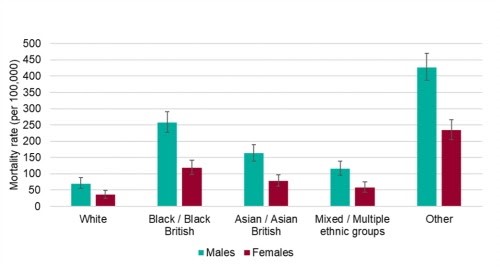

Some data. In England, we have clear evidence that the pandemic has impacted black and Asian people more than white people. People living in the most deprived areas have double the mortality rates than people living in the least deprived.

The mortality rates from COVID-19 are highest in Black and Asian ethnic groups.

The COVID pattern reflects the long-standing and persistent inequities in care. We highly recommend the Institute of Health Equity’s report Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review, 10 years on. It shows how, pre-pandemic, improvements in life expectancy had stalled since 2010. The more deprived the area, the shorter the life expectancy. In fact, this gradient has become steeper; inequalities in life expectancy have increased.

The mode of action of racism

How does racism create inequity? A first step is to understand more about the experiences of discrimination, and how it contributes to worse health.

Racism manifests in a host of micro-assaults, stressors or aggressions that minorities experience on a pretty constant basis. The aggregate effect is disillusionment, lack of confidence, anger, lack of engagement and belief in the system, resentment and adverse performance. All of these hugely impact work, health and patient care.

The mode of action of racism: the aggregated effects of continuous exposure to micro-assaults, stressors or aggressions.

In the workplace, discrimination takes on all of these forms and more. The NHS staff survey {ref needed] shows that BME staff consistently experience more discrimination at work than their white counterparts. If we look more closely at the patterns, we see that the more BME staff experience discrimination, the lower the levels of patient satisfaction. We conclude that the experience of BME staff is also a very good barometer of the general climate of respect and care. Tackling inequity benefits everyone.

Of course, data is invaluable in maintaining the focus on equity. Data helps enormously in keeping organisations’ attention and helps to measure progress. NHS England uses the Workforce Race Equality Standards WRES) to provide indicators of workplace experience and opportunity in NHS England. In this blog for the King’s Fund, Yvonne reveals that the gap between BME and white experiences for WRES indicators 2, 3 and 4 is closing (or it was, before the pandemic hit). This seems like a reason to be optimistic.

So how can I help?

So we move on to some practical strategies to reduce inequity.

We can all start some simple steps to reflect on our own setting:

- Further explore your own biases https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html

- Advance conversations in your organisation

- Educate team members

- Review our policies/practices/data collection with an equity lens

- Review stratified data

- Plan tests of change based on inequities in your system

Above all, we can all be an ally against inequity. Consider the six As:

- Do you have the Appetite for the complex, emotive world of race equality?

- Ask questions about race, be curious, read, learn and educate yourself

- Accept there really is a problem

- Apologise and sympathise, show that you understand racism affects people of certain races

- Don’t Assume you know the answer. Instead, develop informed views bu seeking to understand individuals

- Take demonstrable Action and be accountable.

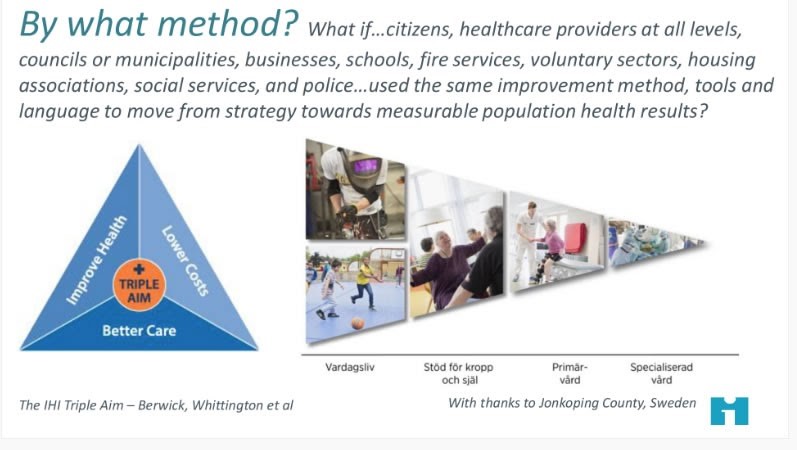

B9: Hands on, place based in pursuit of the Triple Aim – improving population health

Dominique Allwood, The Health Foundation, England

Kristine Binzer, Bridge for Better Health, Region Zealand, Denmark

Pedro Delgado, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, USA

Jesper Ekberg, The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Sweden

We move on now to look at some concrete examples of innovation with equity at its core. We might reasonably subtitle this session as “working in partnership to achieve population health improvement”.

This session was about how we build the bridge between where we are with population health and where we want to be.

We need to deploy our improvement methods in psychology, systems thinking, understanding of variation and iterative learning to this task. The team outlined the key steps as:

- Define the population and design accordingly

- Act with and for the population

- Develop both bold ambitions and bold aims

- Design a learning system for a portfolio of projects focused on each population health aim

- Segment for equity

- Measure what matters

- Embrace and assets-based approach

- Test your way into better partnership work, in pursuit of results

- Make health improvement everybody’d business and make improvement skills available to all

- Embrace humility to generate trust.

Interested in improving population health?

Missed out on our session on Hands on, place based in pursuit of the Triple Aim – improving population health?@MarkOneinFour has done a great thread of key messages #Quality2020 https://t.co/wYlKQHEYz0 pic.twitter.com/aUDCLvi4gv

— DrDominiqueAllwood (@DrDominiqueAllw) November 4, 2020

Kristine Binzer from Denmark gave an account of how this approach was applied to homelessness in Denmark. By exploring these people’s stories, the team realised that what they needed most was “help with the system”. So they developed and rolled out a programme of community members acting as “Travel Companions” to 200 participants. They found improved overall health, improved individual outcomes, for the same financial outlay. Costs were shifted from treatment to prevention services.

Jesper Ekberg said that in Malmö Sweden, the approach was applied to the challenge of high unemployment and low participation using “Activity Houses” based around local schools. What matters to the children and families is put first, and building services around trusted institutions (schools). Activities are free, available year round. A similar, place-based integrated approach is used in Family Centres in Jönköping County. Women’s and children’s health services, pre-school and social services are all brought together under one roof.

Dominique Allwood wrapped up by talking us through an example of an “Anchor Institution” from secondary care in the NHS. Anchor institutions are large, public sector organisations that are unlikely to relocate and have a significant stake in a geographical area. The size, scale and reach of the NHS means it influences the health and wellbeing of communities simply by being there.

Four Pillars of population health improvement (Allwood)

The scale also influences the improvement methods needed. Here, Allwood and colleagues are using:

- Community organisations to understand their interests and how they relate to the organisation

- Behavioural insights to influence behaviour

- The Double Diamond approach to strategy development

- Think big, act small to encourage people to take the first step

In conclusion, we reflected that the job of quality improvement just got more complicated. Not only do we have to do the job and think about how to improve it, we also should be thinking upstream about prevention, who is not thriving, where are the gaps. Building on existing trusted relationships will make it much easier to engage with communities and “build the bridge” towards population health improvement.

References

Cleveland Manchanda EC, Sanky C, Appel JM. Crisis Standards of Care in the USA: A Systematic Review and Implications for Equity Amidst COVID-19. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020 Aug 13:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00840-5. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32789816; PMCID: PMC7425256.

de Lusignan S, Joy M, Oke J, et al. Disparities in the excess risk of mortality in the first wave of COVID-19: Cross sectional study of the English sentinel network [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 25]. J Infect. 2020;4817. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.037

IHI resources on Equity: http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Health-Equity/Pages/default.aspx Accessed 3rd November 2020.

Institute of Health Equity. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review, 10 years on. Health Foundation, accessed 3rd November 2020

Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, Okoye GA, Linos E. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Sep;183(3):593-595. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19258. Epub 2020 Jul 16. PMID: 32471009; PMCID: PMC7301030.

Pan D, Sze S, Minhas JS, Bangash MN, Pareek N, Divall P, Williams CM, Oggioni MR, Squire IB, Nellums LB, Hanif W, Khunti K, Pareek M. The impact of ethnicity on clinical outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Jun 3;23:100404. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100404. PMID: 32632416; PMCID: PMC7267805.

Razaq A, Harrison D, Karunanithi S et al. BAME COVID-19 DEATHS – What do we know? Rapid Data & Evidence Review. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine COVID-19 review, 5th May 2020. Accessed 1st November 2020.

Reed S, Göpfert A, Wood S, Allwood D, Warburton W. Building healthier communities: the role of the NHS as an anchor institution

Last updated: 4 November 2020, 16:22 GMT

Author: Douglas Badenoch, Beyond the Room

SHARE THE BLOG: